| |

from

F. Di Blasi, “Person or Digital Self? An Argument against

AI Theories”

Naturalistic

Period and the Concept of Becoming

Fulvio Di Blasi

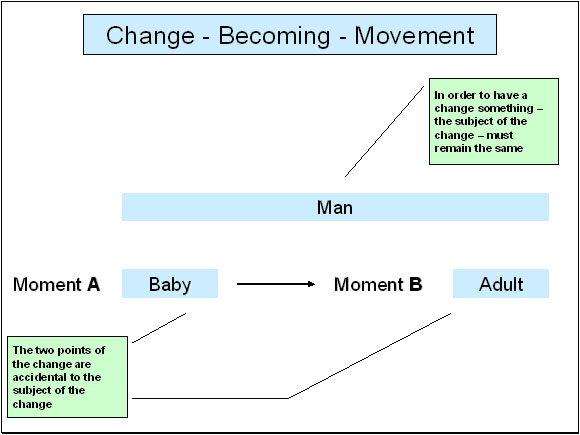

Philosophy was

born in Greece as philosophy of nature when some brilliant

thinkers of the seventh century before Christ began to search

for a principle of intelligible unity in the variety of physical

phenomena. These thinkers realized that no change, or becoming,

could ever happen without the simultaneous presence of something

that does not change and become. It was a logical insight:

if something moves from position A to position B—or from moment

A to moment B; or from situation A to situation B—that something,

as the subject of the movement, should necessarily be the

same thing in both positions A and B; and the movement

should be accidental to it. Every movement, in other words,

is always predicated of the same subject.

Slide

If we want to

logically talk about “change” in case of substantial movement,

for example the death of a man, we have to predicate “change”

either of the soul (which from existing with the body begins

to exist separately) or of the matter (which used to compose

the body and now is decomposing into something else).

The concept opposite to “change” is “creation.” In case of

creation there are indeed different subjects in the two moments

A and B; but, in point of fact, talking now about two different

moments is logically incorrect because two moments must necessarily

belong to the same unity. It is for this reason that Thomas

Aquinas vigorously stated that creation is not a movement,

because there is absolutely nothing before creation: nothing

that can change, nothing that can remain the same, nothing

that can pass from moment A to moment B.

[1]

By observing movements in a natural world in which it seems

that every-thing can change into every-thing else, pre-Socratic

philosophers began to wonder about the first subject of those

movements, or, that is the same, about their substratum or

cause: They started to look for the principle of unity that,

by always remaining the same, makes all changes possible.

Their insights soon moved forward, from the idea of a simple

material principle to a principle that is also efficient,

formal and final. In fact, the efficient cause too must transcend

the single movement, as the efficient cause is the cause that

leads A to B, and that consequently can be limited to neither.

The form, or nature, must transcend each movement as well;

otherwise there would be no proportion between A and B, and

everything could become everything else without continuity:

from the human baby to the adult horse, etc. The same transcendence,

finally, must hold for the end, understood as the conclusion

of the movement determined by—or already inscribed in—the

form of the subject: so, ‘being adult’ must be already present

in the baby’s nature as the termination of the movement.

[2]

The insight on the existence of an intelligible unity behind

the diversity and plurality of changes was certainly easier

in the case of purely physical phenomena than of human phenomena,

in which freedom comes into play. In a sense, it was normal

for philosophy to start as philosophy of nature. For moral

philosophy to start, we had to wait until Socrates, in the

fifth century before Christ.

[3]

|

|